Elaine Summers

Elaine Summers

So Low

Self-Produced

Perhaps the greatest satisfaction that one who does what I do (and what is that you may well ask) can derive from such endeavors resides in those uncommon occasions when a “new” (to me and you) talent is uncovered. Personally, I consider it to be a rare privilege.

And such is my pleasure upon discovering for myself one Elaine Summers. For in the sparse settings given the seven songs (all of which she wrote or co-wrote), there pervades evidence of a very unique and special talent. .

From the first evocative strains of “These Days”, one is transported upon the jagged edge of Summers‘ voice—soft and monotonal at first, like Suzanne Vega; bursting to flame in the choruses: smoking like Melissa Etheridge. But Elaine is no imitator, hence such comparisons do her an injustice. The arrangement here is just a couple of acoustics, a tambourine, and a bass—over which Elaine weaves a tale of desolation and maturity gained through hardwon personal struggles. A piquant little masterpiece. J angled and frazzled. A dusty gem.

“We All Want” continues the mood of anomie, this time to the accompaniment of additional drums, percussion, and keyboard string pads. But the focus is not lost. Elaine brings to mind many great contemporary singers—among whom she herself may rank. For it seems true that she could be fronting Concrete Blonde or the Divinyls as well as anyone else. Yet Summers’ is a more restrained sound, rooted in her acoustic guitar and gentle approach to a song. She only seems to shout (and she can shout) when she doesn’t think she’ll be heard otherwise. “Every Word” is kind of Fleetwood Macky kinda Indigosy. Perhaps a diversion.

“Times Two” walks Blonde pavement in its stark terrain and bleak view. And there’s Juliana Hatfield standing on the corner. Elaine’s got her hands in her pockets, head down, striding right past them all; an air of barely restrained violence hovering ominously above her like a dark gray cloud. Thunder rolls. Lightning kisses the sky.

“ls That Right” surveys the surroundings in a witchy season, questioning the perspective. But with the simple “Life”, her voice a ragged whisper, Elaine wrings this song of her soul into a twisted knot, sounding like an angel encased in a thick coat of ice, singing “Sometimes I feel like a gun and I want to shoot my way right out of here”. Harrowing. Sad. “Flowers” is an arid bouquet placed upon the grave of something no longer alive—as dry as the ash of bone.

So Low would seem to be a work of personal catharsis for Elaine Summers. The sense of numbed emotion and uneven scars upon the psyche, which she conveys, is as terrifying as it is familiar. One would hope that a talent as bountiful as her own would one day find a sense of personal harmony. Whatever the case, Elaine Summers has the ability to express herself in an exceptional fashion. That is her gift—and her curse perhaps.

Pop Theology

Pop Theology

“There is Something”

Self-Produced

Points for originality in promotion go to the Theologians, intent upon releasing a new cassingle every month or two for, I dunno, a long time to come. Keeps their name in the news if nothing else. “There is Something” is a poppy, springy kinda thing featuring Robert Noel on lead vocals with harmonies provided by vocalist Gina Behrman Noel, lead guitarist Mike Dion and bassist Jonathan Drechsler. The tune maybe has a feel a little like Fine Young Cannibals’ “Don’t Look Back” with Robin Thompson or Richard Butler doing the vocals. It’s a crisp, tight production comprised of lots of acoustic guitars over the standard backdrop. Producer Steve Hale (formerly of the band RIA) stays true to the band and the songs’ “Words of Love” sentiment. It’s Buddy Holly for the 90s. It could work.

Susan Martin

Little By Little

Another newcomer, not without considerable talent of her own. Martin’s voice resonates with a round, full tone similar in texture to the uvulations of l0,000Maniacs’ Natalie Merchant. Her songs have a woody hominess about them, warm as jam on a fresh toasted muffin, loaded with butter. “Starstruck” has a certain James Taylor meets Carly Simon quality, coupled with Martin’s propensity for the Dan Fogelberg warble: identifiable by its incessant hoarse intervals, typically employed to attract stray suitors with its wistful bathos. How- ever, more highly evolved members of the species have exhibited a repulsion to such tactics—and as such, Susan might consider ditching what was an antiquated piece of histrionic affectation long before Justin Hayward died his moody blue death.

“And You Danced” gives promise that Martin can sing free of the constrictions of a posture. Similarly, the lyric seems less reliant on tattered cliché and tired homilies— seeming to be a more honest expression of real feeling. I would encourage Susan to pursue this element in her craft.

For too often she relies upon a means of expression that was worn out long before Oz never did give nothin’ to the tin man. Muskrat love. It is one thing to play it musically safe. It is quite another to be conversing in a dead musical language. Great poets, from Emily Dickinson to Virginia Wolff to Anne Sexton are out there for anyone to explore as inspiration for new and rich ways to delineate the human condition. I encourage such an expedition to any hopeful writer.

For “My Fathers Eyes” is so redundant, why it’s redundant. It’s not as though Martin isn’t sincere. But maybe she’s so gol’ darn sincere that she’s squeezed every dram of emotion right out of her presentation. And if her intentions weren’t so pure, and if the possibility of her talent weren’t so obvious, I’d say bag this. But Susan, you must think in other categories. You must challenge yourself not only to demonstrate your feelings, but to feel them as well; to not only express your emotions, but to articulate them as well. Think about it.

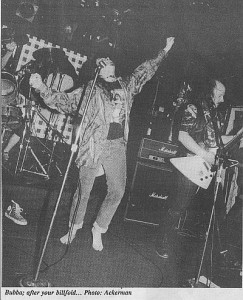

Bubba

Emma

Here’s a hard charging unit who combine positive elements of grunge, Faith No More-like thrash and Ramonesy Trash. A tasty combination immaculately articulated by Mark Laskowski on guitar. Jim Normandy on bass and J .R. Ericksen on drums. Vocalist Doug Smith has the chops to stay right on top of it all. Check out the nasty square dance in the middle of ”What’s Inside”, a seething piece of raunchy sinew. And the lip-curling snarl of the ldolesque chorus! Yow!

These boys can scorch.

Or check out the droogy drang and head banging two-step of “Kill Me”, whose sarcastic death-metal chorus closes the coffin lid on the entire genre. “Laura’s New Car” combines the evil lncantations of Black Oak Arkansas’ Jim Dandy with the swagger of Steve Tyler, unleashing a hard pumping Steppenwolf from the absolute pits of Hell. So tight, your blood will squeeze into your brain and pop like a tie under a match-head.

Or check out the droogy drang and head banging two-step of “Kill Me”, whose sarcastic death-metal chorus closes the coffin lid on the entire genre. “Laura’s New Car” combines the evil lncantations of Black Oak Arkansas’ Jim Dandy with the swagger of Steve Tyler, unleashing a hard pumping Steppenwolf from the absolute pits of Hell. So tight, your blood will squeeze into your brain and pop like a tie under a match-head.

“Don’t Touch Me” pretty much mops up any remnant brain cells with a searing frontal attack, sporting a touching anti-social message from your sponsor delivered with the sensitivity of a steel toed boot.

But dig it. These guys execute their material with Kevorkian precision. You won’t even know you’re dead. Boom. Without a doubt, Bubba are one of the tightest young thrash/metal bands to enter the scene in along time. They are not rookies. They are simply some mutant recombinant come to take possession of your brains and your billfolds. Flee. Flee poor earthlings, you are helpless beneath their withering powers. Flee Bubba now or succumb.

Haunted Homes

Trouble in the House of Fun

Trippy rappy funk. Well produced. Check out the sons of Gil Scott-Heron on “Rad Radio”, broadcasting in a Zappa time zone. “Strike a Match” lumbers in a limber meringue: timbale shots titling between the ears as big as a fist. Heady but original and dynamic. Thoughtful and meaningful. What a concept. Accessible. yet dense. Provocative yet friendly. Intense yet dippy.

A rabidly radical political stance. just to the left of grouchy Karl Marx- invests Mr. Homes‘ postulations with a naive urgency–which is lost in the Freudian fog of “Fear of Trains”: a tune which, save for its jaunty beat and production sheen, otherwise sucks. And takes a long time in doing it.

“Police State” evokes the time-honored demon of the boogie man with the badge. your worst nightmare. in this case sophomorically, even if undeniably accurately. Hell, the Beach Boys covered the same turf in 1971 with “Student Demonstration Time”.

Mirage

Mirage

Invoking the muse of Yngwie, big-balled hair metal. Clean, crisp, precise. Guitarist Jeff Gilbert has done his homework with a Satrianiesque excursion called “Wild Sun”. The Dreggs’ Steve Morse is recalled as well. By the second number. “Velvet Hammer,” you figure out that this is an instrumental unit. Gilbert uncorks some ornately sublime arpeggios whose lightning infused notes travel faster than my drugged out mind can compute. He does this with electrifying dexterity, that truly rivals that of the aforementioned Gods. Wow. Check out the hyperspeed Brian May-like twin guitar on the homestretch. My God!

Jeff’s supporting cast are no slouches. Hell, they’re genuine geniuses just for keeping up with the guy. Especially Mike Peterson’s drumming. His double kick work is nothing short of exemplary. “Aggressive Xtacy” is Bachian bronto rock—soaring and swooping between endlessly cascading arpeggios. “Autumn Wish” begins in a more relaxed, pensive Spanish guitar setting, recalling the early mood band Jade Warrior. Gradually the technical ante is upped, passing through a pastiche of opposing harmonies, sprinting into an upbeat series of manic bursts, which seem like little more than highly skilled exercises—for which Mr. Satriani is reknowned. Amounting to not a whole helluva lot.

**********************************************************************************************************

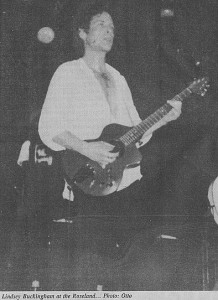

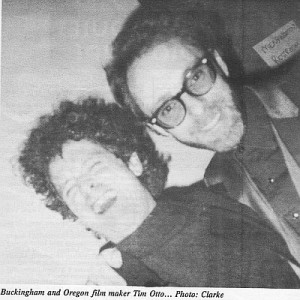

Lindsey Buckingham:

Endlessly Rocking

The guy has tons of bucks, more gold records than this entire city will ever see, and rave reviews over his current tour (with 9-piece back up band) in support of his critically acclaimed album Out of the Cradle. Still, there is something reticently quixotic about Lindsey Buckingham. Perhaps it’s his laid back 60s Californian roots, or perhaps a certain ambivalence borne of his five year hiatus from the rock limelight. Whatever it is, Buckingham does not seem as self-satisfied nor as ego-inflated as he might have the right to be. What follows are excerpts from a rambling 80 minute conversation I had with Buckingham recently, just as he was about to embark on tour.

Q: What with the crack backup unit you’ve assembled for this tour, have you given any thought to forming a band?

Oh I don’t know. I guess it all depends on what you call it. I think that when I go back into the studio I might work with other musicians. It really gets down to relinquishing control. There’s a lot of great talent in LA. But it’s hard to find the right people–who can take direction and aren’t on some trip of their own. That’s why I’m so happy with the band I’ve got for the tour. It’s a very harmonious group.

But up to now I’ve wanted the control —concentrating on one or two songs at a time. I didn’t really want the input. I was trying to put my ide- as down as I conceived them. That seemed to be the way to do it. But now that I’ve done that, it feels right to try something else. I think I’m ready to start relegating some of the responsibility.

Q: Was that your role in Fleetwood Mac?

No (laughs). I don’t think they wanted that. They were looking for someone to fill a space when they heard our tape (Buckingham Nicks, 1973). They needed singer/songwriter/producer types. Front people. That was the hole that needed to be filled.

Q: Where would you be now if Mick Fleetwood never would have auditioned Buckingham Nicks?

That’s a very good question. And don’t think I haven’t contemplated it a lot over the years. Stevie and I were having some real management conflicts at the time. The album wasn’t doing real well and they were trying to get rid of us. They were trying to book us into, like. steakhouses. Like a one way ticket to Palookaville. We avoided that, thankfully. But there was the East Coast and pockets of the South–they were all college towns that had responded to our record. We were generating sales, and instead of opening for somebody bigger–we were playing to crowds of four or five thousand as the headliners, so we knew there was a discrepancy between what we were being told and how we were being treated in LA, and what we were seeing for ourselves. We didn’t know what to think.

And then Fleetwood Mac came along and we really didn’t know what to think. It wasn’t like “Oh wow, this is great!” because we were seeing some success on our own. And there was the possibility we might have made it. It’s hard to say what might have happened. Maybe we would have starved. Believe me, I don’t regret anything that happened. It was amazing, it really was.

Q: Was there an event or moment when you knew you wanted to be a musician?

Q: Was there an event or moment when you knew you wanted to be a musician?

Well, I remember my older brother saying “Hey there’s this real cool guy, Elvis Presley”. And I’d been listening to the radio, you know Patti Page and Gogi Grant “The Way- ward Wind” and all that. But Elvis was such a revelation. And that was probably a pretty common experience in this country at that time. He kind of became a role model. And I’m sure a lot of kids ran out and bought guitars because of him.

I was sort of fooling around on guitar before that, but it locked me into an idea. I got a book and started learning the chords and all the positions. But otherwise, I’m pretty much a self-taught musician.

Q: Do you remember the first song you ever wrote?

Oh (groans)…gosh. I don’t want to talk about that. I didn’t start writing until alter I met Stevie. When I met her, she’d already written fifty or sixty songs. I didn’t write any until I was, like, 20 or 21.

Q: Are you prolific? Or is song- writing a labor of love?

Well, it’s a labor. A labor of hate. There are times when I’m prolific. It depends on the mood. I mean there were a few years there when I’d walk through the studio in my garage and say “Yes. There it is,” and keep on walking. I didn’t even want to think about music. A lot of times I think of general ideas and start building from there.

Q: What were your goals and aspirations when you started out in your first band?

Well I had to undergo a lot of deprogramming. Even though I started playing very young and was given conditional approval—l was still kind of doing what was expected of me. My parents encouraged me to play, but they never encouraged me to think of it as a career. And it never really occurred to me then that I might take up music as a, you know, vocation. My parents never considered show business to be a reliable profession. And they were right (laughs).

So what happened was, all through school, I pretty much did what I was supposed to do. Played sports and did the school thing. My older broth- er was an Olympic swimmer in 1968…

But when I got out of high school and started college, in 1968, there were a lot of changes going on in the world. And because of the cultural thing going on, I had the opportunity to see life differently. And all that programming just sort of went out the window. So I quit sports and grew my hair out.

And eventually, a few years later, all the people in our band Fritz quit college and committed to that. I didn’t really have a career in mind before that. My mom always said ‘Well you like Art (imitates his mother)…’, so I was thinking about something in the Visual Arts maybe…

Q: Any other early influences as a songwriter?

Well it was all of that rock and roll. And I went through a lot of folk influences for a while. But I really don’t consider songwriting to be my forte. I think I’ve been really lucky with what I’ve written. Brian Wilson was an influence when I first started writing songs I guess.

Q: Do you have any favorites among the songs you’ve written?

That’s a tough one. They’re like children, you know? I probably do have favorites. But I wouldn’t want to single any out.

Q: The name Richard Dashut appears on all your records since 1973 both as a producer and co- songwriter.

Oh yeah, we’ve been through it all. He’s been both a friend and a partner for a long time. He’s a very personable guy. And I trusted his musical judgment almost immediately since he was seconding the production on. But he’s a friend first. Stevie and I lived in the apartment downstairs from him when we first moved to LA.

And he’s not overly technical, that’s what I appreciate about him. That and he gets what I’m after without a lot of discussion. We communicate well without a lot of talk. I like that. He intuitively seems to know what I want.

Q: You produced a lot of different acts in the late 70s. Any future plans in that regard?

Well, not really. It took a little longer than I anticipated to get this going. And I really wanted to focus on this project Out of the Cradle and the tour). Once that’s done I might give it some thought.

Q: What’s your approach to production?

My approach is very visual—like canvas and paint. I like a sense of balance and proportion. Elements of texture and contrast play a part. A painting tells you what it needs. Preconceptions fall away. A sense of discovery is enhanced. The sense of chaos is enhanced too. It’s all about trying to balance order and chaos.

I have some of my own approaches to things that are considered to be a little backwards. Or were, anyway.

One approach to recording an instrument is to run it direct and put a couple of mics around it—a stereo recording and mix. And that’s all great but it takes up a lot of space. It gives you a nice kind of shading, if that’s what you want. But I tend to do that almost never.

I usually record only direct and only a mono signal. What it does is allow for more layering. It gives you more space, more single identifiable sounds across the spectrum, and more control over their placement.

I have to laugh. Because if anyone ever saw how I do it, they wouldn’t think it was exactly a state-of-the-art way of doing things. Somebody like Bob Clearmountain laughs at the way I do things—yet the album (Out of the Cradle) got nominated for a Grammy for Best Production. I wanted to call him up and say “Hey!” But what it gets down to is—if it works for you… For me it gets down to space. It’s kind of a contradiction I guess. I want to fill up the space but not crowd it.

If I want a part to sound like stereo, I’ll usually double it. But more often than not I’ll have several separate parts and none of them will play straight through.

Q:Any favorite toys? Instruments?

I’ve got a Takamine nylon string that I use a lot. It’s got a real clear, precise tone, but it doesn’t eat up a lot of sonic space. And I’ve got a Martin D-28 and a Strat that I use a lot in the studio.

I have a rack full of effects that I use, but I don’t need them. And I’ve got both analog and digital recorders in my studio. But I still prefer analog—it gets a certain ambience. I like digital for its simplicity, but it still has this sawtooth sonic quality where analog is more like a wave.

Q: What part of the music business do you dislike the most?

Q: What part of the music business do you dislike the most?

I don’t know. I don’t want to say. It’s like biting the hand that feeds you, you know? But between you and me, I think radio is real hard. It’s just a matter of degrees, but radio these days is sort of like a pinhole that you have to get through and a brick wall on the other side. And anybody who thinks they have it made or all together is humbled, because radio is this machine that’s all its own and it’s, like, humming. Radio doesn’t seem to exhibit the highest level of sensitivity in the industry, I’d say.

Q: What do you enjoy most about the business?

Oh I just think it’s great to be able to have the freedom to be able to express yourself, the oportunity to be creating. To be able to generate a career out of that is astounding to me. I feel very lucky.